Direct Ties

Quakers are often cited as “pioneers in the crusade against slavery” as, by 1784, all American yearly meetings had ruled that no member may be in good standing while acting as an enslaver, the first American denomination to do so (Hamm 33; McDaniel and Julye 3). However, Quakers actively participated in enslavement and the slave trade prior to that date, and as late as 1767, Quakers in Philadelphia were overrepresented in the enslaver population (McDaniel and Julye 6). In order to recognize the later abolitionist efforts of the Society of Friends, it is first important to acknowledge their participation in the American system of enslavement.

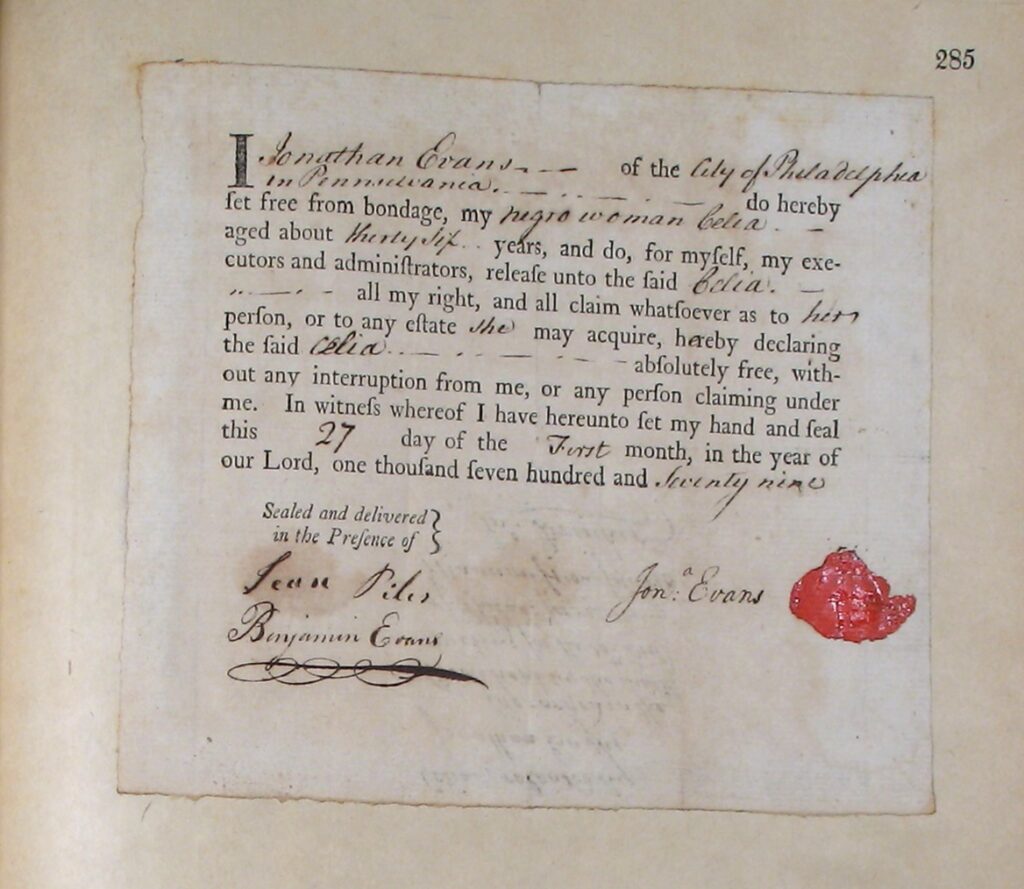

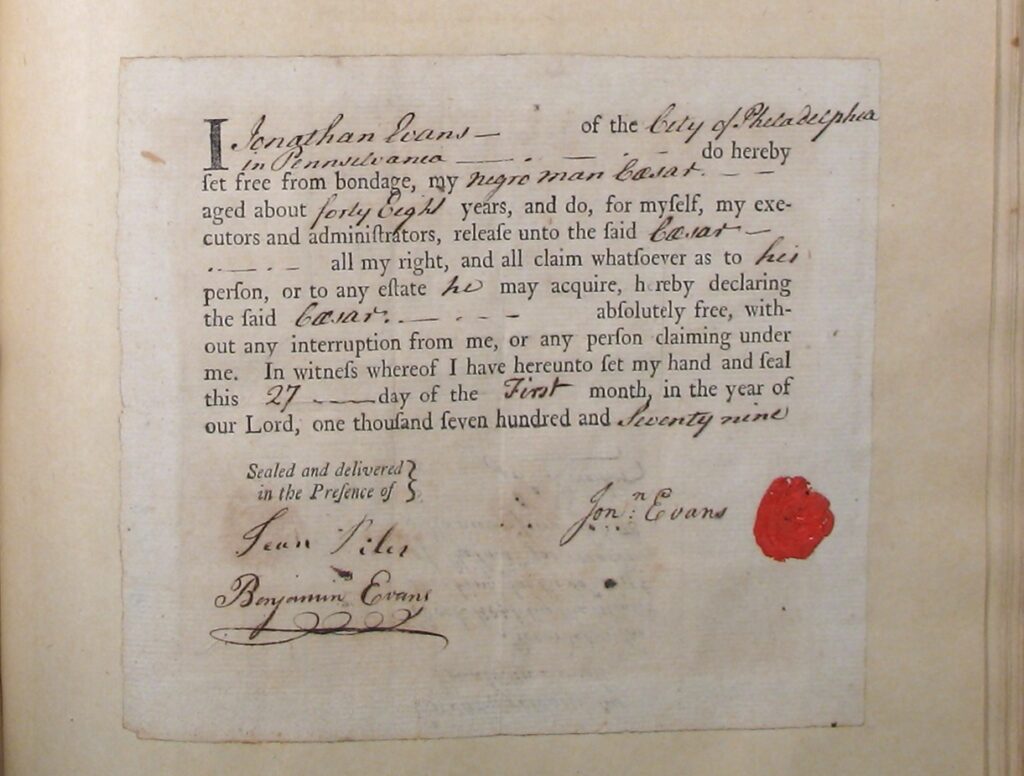

Jonathan Evans (1714-1795) enslaved at least two people, Celia (b. circa 1743) and Cesar (b. circa 1731). Both were manumitted by Evans on January 27, 1779, as witnessed by Jean Piles and Benjamin Evans, Jonathan’s son. Little is currently known about their lives, even as the story of their existence was passed through generations. According to Mary Rhoads Haines in Clovercroft Chronicles,

As the gradual abolition of slavery did not begin in Pennsylvania till 1780, their [Jonathan and Hannah Evans’] household service was performed by negro slaves. Two of them continued in their employment and under the care of the family till after the decease of my great-grandfather [Jonathan Evans, in 1795], and I have often heard my mother and her sister speak of Caesar and Sela. They were husband and wife, and Sela had the reputation of being the best cook in Philadelphia. No doubt her skill contributed largely to the family festivities (183-184).

According to another Evans descendant, Jonathan and Hannah Evans

owned two slaves Peter & Celia. His

Jonathanwidow after his death went to live at 322 Union now DeLancey and took Celia (slave) with her. This slave slept on bed on floor with mistress to tend her through the night. (Evans, Jonathan Jr.)

Though the details of the two descendants’ memories differ, the substance remains the same: at least one person enslaved by Evans remained in the household after they were manumitted. Though this could, as in Haines’ account, be attributed to a paternalistic sense of duty on the part of the Evanses and a familial devotion on the part of Celia, manumission in truth changed little regarding socioeconomic mobility. Formerly enslaved people in Pennsylvania often “became indentured servants under a long-term agreement and continued living with their former owners”; half of the free Black population lived in white households in 1790 (Ross 72). There is not currently any evidence to suggest that Cesar and Celia were indentured after 1779, which likely would have run afoul of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, but the lack of resources available to them would have necessitated remaining connected to the family that once enslaved them.

Some Quakers accomplished this through Committees on Free Negroes that “inspected and settled accounts between the free blacks and their employers,” through compensation for labor performed while enslaved, and through education, religious and academic (Soderlund 179, 182). Whether Evans participated in any of these endeavors is likewise unclear. The truth of Cesar and Celia’s lives likely lies somewhere between the lines; they may have remained with the family both because of a lack of opportunity elsewhere and the particular efforts of the Society of Friends. More research is needed to determine the full extent of their lived experiences.

Economic Engagement

Though Pennsylvania began the process of abolishing slavery in the state in 1780 through its Gradual Abolition Act–a process that would not end until the 1840s–it did not mark the end of the state’s involvement in the long history of enslavement in the United States. Nor did the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s 1776 decision to disown Quaker enslavers prevent members of the Society of Friends from engaging with the products of enslaved labor (Holcomb 37). Indeed, the story of the incredible wealth obtained by Southern enslavers cannot be told without the Northern financing of that labor, their transformation of cotton picked with enslaved labor into usable cloth that spurred a second industrial revolution in New England, or their transport of that cotton and cloth domestically and abroad. According to Edward Baptist, “as of 1832, cotton made by enslaved people was driving US economic expansion. Almost all commercial production and consumption fed into or spun out from a mighty stream of white bolls” (319). Nearly every aspect of the American economy was influenced by enslaved labor, regardless of local laws or abolitionist sentiment.

The same is true of the Cope family. Though current evidence suggests that the Copes did not have direct ties to enslavement in the way that the Evans family did in the late eighteenth century, they nonetheless participated in this economy of enslavement through their business activities. Founded in the early 1800s, Thomas Pim Cope’s shipping business, here referred to by its most prominent name of the Cope Brothers, dealt in a variety of goods, many made with enslaved labor. According to Thomas Cope’s obituary as printed in a November 1854 issue of The North American,

In 1810, he removed his counting house to Walnut street wharf, where he conducted the business of foreign shipping, in conjunction with an extensive and lucrative domestic trade, chiefly from the South. Nearly all the tobacco traffic of the South was then centered in Philadelphia, and the greater portion of this large and profitable staple of Maryland and Virginia, came to the warehouses of Mr. Cope. (Scrapbook of Clementine Cope)

Tobacco produced with enslaved labor therefore set the foundation of the nascent shipping business By 1822, it was transformed into “a full-fledged packet service…by the intervention of Alexander Brown and Sons of Baltimore,” one of the most prominent merchant houses of the time (Killick, 63). As part of that arrangement, the Browns loaned Cope the Unicorn, which the firm had used as recently as 1820 to transport enslaved people from Maryland to New Orleans (Killick 65; Schermerhorn 42).

The Cope business, however, focused on the Philadelphia-Liverpool line, promising fast, regular voyages for cargo and passengers. They shipped a variety of goods, including turpentine, rosin, bark, and grain. Still, when cargoes were light, “the Copes added a southward leg to the transatlantic passage, sending the ships down to the cotton ports” (Killick 70). It is here that the Browns’ expertise was needed, as their Southern agents and connections allowed for well-informed speculative opportunities. The Cope Brothers would load their ships with cotton in Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, and Mobile throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. Liverpool, the most frequent destination of Cope Brothers ships, dealt in all trades, but was a determiner of fate in the world of cotton. When “prices rose in Liverpool, planters in Louisiana might decide to purchase fresh cotton lands, and slave traders might find it profitable to move young slaves by the thousands into these new territories” (Beckert 201). Profits could be increased through further efficiency of cruelty, forcing enslaved people to pick yet more cotton in fear of punishment. The Cope Brothers would journey southward, hoping to join in on potential profits, and transport the cotton to Liverpool, continuing the cycle.

Yet surviving business correspondence rarely directly refers to the enslaved labor that made the entire industry possible. On February 1, 1843, Captain H. F. Miercken of the Thomas P. Cope wrote that

A great quantity of cotton has been sent here, say 20,000 bales, and much more to come from Mobile, the packages are large and soft, not compressed. Mr. Walter told me the evening that many of the planters have left this state and gone to Alabama and having engagements to meet at Charleston, send cotton, exchange being 15 to 20 per cent. (Emlen, 30)

Miercken did not have direct contact with enslavers–“planters”–instead working with agents and brokers who coordinated the sales. Yet his presence at the docks would put him directly in the middle of the buying and selling of enslaved people. Enslaved men, women, and children would have been loaded on and off ships, not unlike Miercken’s cotton, and transported to “slave pens” mere blocks away from the levee in New Orleans (Johnson 2). Cotton prices were discussed alongside the prices of human beings, and the same merchants may have even dealt in both (Rothman 122-123). Miercken, too, had a job to do, and his personal feelings regarding enslavement are unknown.

Familial correspondence suggests that enslavement may not have been such an affront to one’s morals as many Quaker histories would suggest. Writing from Charleston in 1839, Francis Reeve Cope told his brother that

If I was going to write a geography of Charleston I should divide the inhabitants into 3 classes– the whites– the negroes & the turkey buzzards & of the latter two it would be difficult to say which was the most numerous or dirty…I wish I could show thee a picture of some scenes in Charleston in which the negroes are the most prominent objects. To attempt a description would be useless. The women generally wear turbans & some of them wear straw hats on top. They are frequently in very filthy clothing but appear to be contented– I know of no better way of giving an idea of their feelings than by comparing the happiness of the older part of the community to that of a company of hags & that of the latter to a troop of monkeys– one of the most laughable scenes that I have met with while here I see every day just before our dinner time. The dining room is seperated from the kitchen by a yard & across this yard just before dinner comes a procession of blackeys bringing the dishes from the kitchen to the dining room– there are about a dozen of them from the ages of 30 to 80 & they come in the order of their size chattering & jabbering like so many moneys & in going back they seem helter skelter bellowing & hellowing & each one bestowing as many kicks can manage to give on his neighbor ahead– The negroes here are on a much more familiar footing with the whites than with us– We saw them on 1st day coming promescuosly out of church together– all the male part of the community from about 50 down are addressed by the title of boys– the rest of that of old men.

Given the traditional story of Quakers campaigning for abolition and equal rights, one might have expected Cope to comment on the enslaved status of the people he encountered, even if his nineteenth-century mindset prevented a full acknowledgement of racial equality. But Cope, instead, perpetuates the idea of happy, childlike enslaved people. In addition to pointing toward unequal conditions in the North, this account suggests that the Cope Brothers may not have faced a moral struggle as they sought to profit from cotton produced with enslaved labor.

Baptist estimates that in 1836, 600 million pounds of cotton was equivalent to more than six million person-days of enslaved labor picking cotton, a ratio of 100 pounds to one person-day (272). If the Copes transported 1000 bales each voyage weighing 400 pounds each, they would have, in effect, sponsored 400 person-days of enslavement. In actuality, each voyage typically carried between two hundred and thirteen hundred bales (Algonquin), financed not only by the Cope Brothers but also their purchasers. The Cope Brothers, as a relatively minor player in this story of empire and enslavement, did not single-handedly encourage American enslavement, but they did not divest themselves from it.

It cannot be said that the Copes made their wealth entirely or even mostly from cotton as they diversified their business through a variety of goods and services. But it nonetheless contributed to the wealth that allowed Henry Cope to build Awbury, to establish a family home that would serve as the basis of generations of Cope family connections and correspondence, and to invest in stocks and securities that would similarly fund family affairs. Many Cope family letters were sent care of the Cope Brothers and their Walnut Street offices. Their financial status allowed them the security to save this correspondence, allowing future scholars to read and interpret them.

But this wealth also financed other activities. In 1859, Alfred Cope subscribed “to Ellen Fell to purchase freedom” of an enslaved person (Letters and papers of Alfred Cope). In 1862, Henry and Alfred Cope, on behalf of the Cope Brothers, wrote to Abraham Lincoln promising to contribute fifty thousand dollars toward Lincoln’s proposed compensated emancipation scheme in which enslavers would be paid in return for manumitting the people they enslaved. Though this latter sum does not appear to have ever transferred hands, it represents a sustained commitment toward emancipation and abolition. Despite his earlier writings on enslaved people, Francis Reeve Cope would go on to be a member of the Pennsylvania Freedman’s Relief Association and, with the Cope Brothers, help to finance the Penn School on Saint Helena Island, South Carolina.

Still, other members of the Cope family went further in their abolitionist views. Marmaduke and Jasper Cope were active members in the Free Produce Association of Friends of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting which advocated for the purchase of products made without enslaved labor (Free Produce Association of Friends of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting; Quakers and African Americans, L-N). How might the two have reconciled their personal beliefs with that of their family? The two rarely appear in the Cope-Evans Family papers, potentially suggesting a familial rift.

Like Quakers as a whole, the Cope family had a multifaceted relationship with enslavement, and they can be judged only by nineteenth-century notions of morality. The use of and profiting from products made with enslaved labor was not nearly as universally condemned as the direct enslavement of people by Quakers, and abolitionist sentiment did not necessarily correspond with notions of full equality. Current evidence suggests that the Cope Brothers did not directly enslave people, yet they actively participated in an industry that relied upon the maximum extraction of labor for the cheapest price.

The Civil War

The Civil War marked a turning point in Quakers’ broader political participation; according to Tom Hamm, “before 1860, a number of Friends, both Hicksite and Orthodox, had reservations about ‘intercourse with the parties and policies of the world’” (Hamm 186). But while the Civil War marked a Quaker entrance into broader national politics, it did not come without some reticence as Friends “were burdened not only by a traditional hesitancy about political activity but by the thorny question of party loyalty” (Benjamin 75).

Just as Quakers varied in their commitment to abolitionist causes, they varied in their reactions to the Civil War. As pacifism serves as a central tenet of the faith, many “Quaker meetings affirmed their loyalty to the federal government and their support for antislavery but cautioned against taking up arms in defense of either cause” (Holcomb 54). Still, unlike other conflicts, most meetings did not automatically disown those who enlisted (McDaniel and Julye 147).

In August 1862, Alfred Cope received a letter from Charles Drinker requesting that Cope, perhaps through his business connections, “procure for [him] a situation in the Navy as Captain’s Clerk.” As the only male available to care for his family, his mother and sisters objected to his desire to enlist in the Army, but the threat of a looming draft made them “feel satisfied” at the prospect of the Navy “as the service is not so hard.” A captain’s clerk, or yeoman, would primarily perform administrative tasks and thus not engage directly in violence.

Thomas Evans (1798-1868), on the other hand, lobbied government officials regarding drafted Friends. First with other Quakers and then alone, Evans wrote Edwin Stanton, then Secretary of War, regarding six Quakers between 1863 and 1864: five North Carolinian Friends forced into the Confederate Army and held as prisoners of war, and one Pennsylvanian Friend drafted into the Union Army despite a medical condition in addition to his conscientious objection. However, in an August 1863 letter, Evans took pains to emphasize that members of the Society of Friends did not object to the war because it did not agree with the federal government, but rather that they objected to war itself:

It is true Friends cannot fight for the Government, but they are thoroughly loyal to it, and desire to uphold in every way they conscientiously can, the great principles of order, subordination, and religious, civil and natural right and liberty, involved in the present struggle and their moral influence is not wholly unavailing. Even in the Confederate States, so called, Friends do not sympathize with the Rebellion but deplore and condemn it and would gladly see the Union restored on the basis of universal freedom; I do not know of one member of our Society in any one of the free States who entertains a sentiment in the least degree favorable to the Secession.

Evans, grandson of the Jonathan Evans that enslaved and manumitted Cesar and Celia, believed wholly in the concept of freedom for all. Though Quakers continued to hold a wide variety of views concerning the Civil War, its causes, and its effects, by 1861 most agreed that abolition was a necessary act.

Bibliography

Algonquin. Thomas P. Cope packetship logbooks, HC.MC.975-11-009, Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

Baptist, Edward E. The Half has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Emlen, Arthur, ed. Voyages of the Packet Ship Thomas P. Cope, 1839-1846. Lake Oswego, Oregon, 1999.

Evans, Jonathan Jr., 1759-1839, 1780-1897. Evans Family Papers, HC.MC.1007, Box 1, Quaker & Special Collections. Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

Free Produce Association of Friends of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. HC.MC.975-09-011, Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

Haines, Mary Rhoads. Clovercroft Chronicles, 1314-1893. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1893.

Hamm, Thomas. The Quakers in America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006.

Holcomb, Julie L. “Quakers and Reform in Nineteenth-Century America: Friends’ Response to Antislavery, Women’s Rights, and the American Civil War.” In The Creation of Modern Quaker Diversity, 1830-1937, edited by Stephen W. Angell, Pink Dandelion, and David Harrington Watt (University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2023), 37-57.

Johnson, Walter. Soul by Soul: Life Inside the antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge, MA: Harvard College, 1999.

Killick, John. “An Early Nineteenth-Century Shipping Line: The Cope Line of Philadelphia and Liverpool Packets, 1822–1872.” International Journal of Maritime History XII, no. 1 (2000): 61-87.

Letters and papers of Alfred Cope, 1836-1864. Thomas P. Cope Family papers, HC.MC.1013, Box 2, Folder 4, Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

McDaniel, Donna, and Vanessa Julye. Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship: Quakers, African Americans, and the Myth of Racial Justice. Philadelphia: Quaker Press of Friends General Conference, 2011.

Quakers and African Americans, L-N: Maier- “Free Produce Association” 1840s and 1850s, 1845-1910. Taylor Family papers, HC.MC.1179, Box 1, Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

Ross, Marc Howard. Slavery in the North: Forgetting History and Recovering Memory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Rothman, Joshua D. The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America. New York: Basic Books, 2021.

Schermerhorn, Calvin. The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815-1860. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Scrapbook of Clementine Cope, 1844-1903. Woodbourne Orchards and Family of Francis R. Cope, MC.1230, Box 3, Quaker & Special Collections, Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

Soderland, Jean. Quakers & Slavery: A Divided Spirit. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.