Key Family Members

Thomas Pim Cope (1768-1854), was a prominent Quaker merchant who was actively involved in the economic and social development of Philadelphia. Born in 1768 to Caleb and Mary Mendenhall Cope in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, he arrived in Philadelphia between 1785 and 1786 “to commence the acquisition of practical mercantile knowledge” (Chandler 358). He became a partner of Mendenhall & Cope in 1788 before beginning his own retail business in 1792. His primary success, however, came in the form of his shipping business, later known as Thomas P. Cope & Sons. During his life, he served as a member of the Philadelphia City Council, Pennsylvania Legislature, and President of the Mercantile Library Company, and provided financial support for the Pennsylvania Railroad. Cope identified as an Orthodox Quaker (Baltzell 501, 440-441; Barbour and Frost 187).

Henry Cope (1793-1865) was the son of Thomas Pim Cope. With his brother Alfred (1806-1875), he continued the family shipping business as H & A Cope beginning in 1829. In 1854, he established the Awbury family estate in Germantown.

Francis Reeve Cope (1821-1909), the grandson of Thomas Pim Cope and son of Henry Cope, was a merchant and businessman, having taken over H & A Cope as the Cope Brothers. He was involved with the Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association, a philanthropic effort established around 1862 to provide education for freed persons (Benjamin 76, 140-141, 128).

Jonathan Evans (1843-1911) was the fifth child of Thomas Evans and Katharine [Catharine] Wistar. He married Rachel Reeve Cope (1850-1939), daughter of Francis Reeve Cope, in 1873, uniting the two prominent Quaker families. Evans served on the School Committee at Haverford College for nearly thirty years. (Evans 138).

Clementine Cope (1835-1903) was the oldest child of William D. Cope (1798-1873) and Susan Newbold. She had two brothers, Edgar and Alexis, and had a close relationship with her sisters, Caroline and Annette. Clementine never married, but traveled often throughout her lifetime and served as a teacher under the Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association.

The family maintained a close network of correspondence at home and abroad. Reports on the health of family members, stories of birthdays and weddings, and details regarding child care and chores were all important subjects in letters written by the women of the households.

Issues regarding religion, however, are less frequent in female correspondence. While male Evans family members were at the center of the Hicksite-Orthodox schism–for example, Philip S. Benjamin suggests that while Quakerism embraced egalitarianism and “offered opportunities for women in the ministry”–Philadelphia Quakers grappled with the issue of “grant[ing] women equality in the administration of their Meetings.” Outside of the Meetings, Quaker women took roles as nurses, teachers, and social workers, while men often served on charity boards. Benjamin also notes that “two-fifths of the women in Philadelphia meeting never married” (Benjamin 148, 164, 148-169).

The families’ domestic lives, especially that of the female members, lead to many more questions of scholarly inquiry. For example, in what ways was Clementine Cope, a Quaker woman who never married and spent time abroad, representative of women during this period?

Key Locations

While the bustle of city life served as the arena for business affairs and reform efforts, letters written by the Cope and Evans families from Awbury and Woodbourne captured scenes of life at home. The origins and destinations of these letters reflect the evolving familial and geographic relationships of a close-knit Orthodox Quaker family.

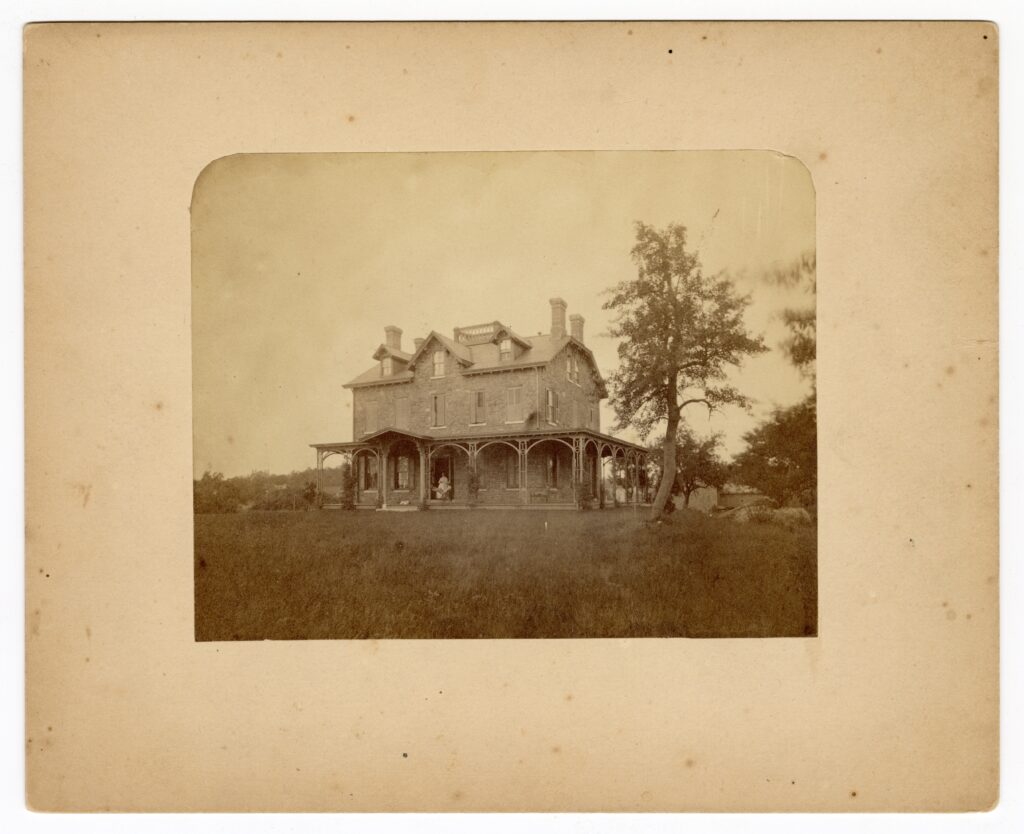

Awbury, the Cope family estate for four generations, consists of multiple houses. Established in the early 1850s by Henry Cope (1793-1865), the 40-acre Germantown estate was named for the ancestral family home of Avebury, England, and originally intended as a summer home for Cope, his children, and his grandchildren. By 1861, however, the family was living at Awbury full-time, and a second house was constructed for the family of Henry’s son, Francis Reeve Cope (1821-1909). Francis’s brother, Thomas Pim Cope II (1823-1900), occupied the original house. As the family grew in size, additional homes were constructed, including for the families of Rachel Cope Evans, Mary Cope Haines, Alexis T. Cope, and Eleanor Cope Emlen (Scattergood 2, 41). In 1916, a portion of the property was donated to form Awbury Arboretum.

Woodbourne served as another, more remote family estate in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, near Dimock. The property was transformed into a summer home by Alexis Cope (1850-1883), but had been in the family since at least the late 1820s when his father, William Drinker Cope, began supervising and leasing a 25,000 acre tract for Thomas Pim Cope (Papers relating to Woodbourne Orchards). Woodbourne served as a retreat for many members of the Cope family who hoped to escape the summer heat in Philadelphia and also included an orchard and a working farm. In 1956, 630 acres were donated to The Nature Conservancy to be maintained as a nature preserve in perpetuity.

Connymead, located in Overbrook, served as the home of William Drinker Cope (1798-1873) and later his daughters, Caroline (1840-1944), Clementine (1835-1903) and Annette Cope (1843-1916). While it neighbored Edgar Cope’s Fellsworth, unlike Awbury and Woodbourne, it did not serve as a family refuge. Clementine lamented the relative isolation of the home, advising her brother Alexis that “Connymead is no place for any body to live who wants to be a Friend, or who has any preference for their ways. Life there was a continual struggle [which] I have no desire to renew.” The property was sold by Alexis T. Cope in 1882.

Notably, the Cope-Evans family, unlike many Orthodox Quakers, largely did not live in Philadelphia itself, instead preferring suburbs like Germantown and Overbrook. Before venturing to seaside resorts for fresh air in the postbellum period, they established summer homes and country estates to separate themselves from the busy and physically unclean life of the city.

Beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, “English officials and German merchants came out from Philadelphia [to Germantown] in summer to enjoy the fresher air and to get away from the city’s ‘miasmas,’” a flight that only intensified with the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 (Tinkcom 166; Holst 4). For wealthy families such as the Copes,, “the country house served as an antidote to the city, providing healthful air, physical exercise, mental restoration, philosophical contemplation, and delightful views of nature” (Holst 39). The sprawling, picturesque lawns would have also provided opportunity for family members to express their horticultural interests, as did Woodbourne for naturalist Theodora Morris Cope. In Germantown, the Cope-Evans family could build houses as their lineage expanded. They could raise their children together and live in community with one another. While the Cope-Evans family is often considered a Philadelphian family, their specific relationship to the city is defined by their ability to move away from it; though they continued to engage in business and philanthropic endeavors, their wealth allowed them to experience city life at a distance.

Supporting the Family

The families employed a number of workers within their homes. According to Elizabeth Stewardson Cope (1848-1937) in her Reminiscences of My Youth, in 1854,

there were ten servants in all. Grandma [Rachel Reeve Cope (1794-1863)] had four–a cook, assistant cook, a chambermaid, and waitress. Aunt Lizzie [Elizabeth Waln Cope (1823-1902)] had 2 nurses and my mother [Anna Brown Cope (1822-1916)] two, and there were 2 colored men, Anthony Ballard, Grandpa’s [Henry Cope (1793-1865) coachman, and William Trusty, who was then only a boy of 15, but remained in our family for many years.

Anna Brown Cope “always kept a colored cook and waitress though our nurses were white,” while Rachel Reeve Cope “kept three servants. A cook and a chambermaid, who were generally Irish, and an old colored woman named Jane Potts, or ‘Jinny Potts,’ as Grandpa always called her.” While the Cope-Evanses occasionally hired extended relatives or friends of the family, the majority of those employed at Awbury were Black or Irish. The hiring and firing of these predominantly female workers was a frequent topic of conversation, reflective of the national anxieties regarding the so-called “servant problem” of the late nineteenth century (Philips-Cunningham 15).

In Elizabeth Stewardson Cope’s account, as in surviving correspondence from the family, there appears to be a preference for white nurses for Cope children, while Black workers were often relegated to the work of maids and cooks. Such a preference may have related to the specific duties of the position. Caroline, for example, an “English girl” who cared for Elizabeth as a child, “could read intelligently and generally entertain” Elizabeth and her siblings better than her other nurses. This governess-like position would have required greater education than was often available to Black women in the nineteenth century.

Yet Irish servants were not viewed as equal, either. In November 1880, Alexis T. Cope wrote to his wife Elizabeth (“Lilly”) that he wished “all the Irish, Protestant and Catholic, could be shipped back to their native land. Common sense, which has long been knocking at the kitchen door, would then have a chance to enter the household.” A few days later, he again wrote

I say, down with the Irish! There is no people on the face of the earth more unsuited to make satisfactory “helps” in American households. Their characters are too untutored, too mercurial, to breathe Republican air with any degree of acceptability to their employers.

The lack of native-born white domestic workers formed the core of the servant problem. Though the Copes had previously donated to Irish famine relief efforts, they shared many Americans’ views in their stereotyping of Irish women as brusque, violent, and unrefined.

Even still, it is these primarily female workers who made the Cope-Evans family’s way of life possible, even as they rarely appear in correspondence beyond decisions regarding their employment. They cooked meals, cleaned the vast estates, and cared for the physical, emotional, and educational wellbeing of the children. In so doing, the family was free to continue their extensive correspondence, to travel, and to engage in religious and philanthropic efforts. Despite technological advances, this work was often physically strenuous and required one to work more than ten hours per day, seven days per week (Lynch-Brennan 104).

Correspondence and census records indicate a number of additional workers living at Awbury, many of them Irish. More research is needed to determine other people employed by the Cope-Evans family, their backgrounds, and their experiences within and beyond the Cope-Evans household.

People Employed by the Cope Family, as Recollected by Elizabeth Stewardson Cope

Anthony Ballard, Black, coachman

William Trusty, Black, “chore boy” and coachman

Ann Taggard, cook

Bridget, Irish, cook

Jane “Jinny” Potts, Black, “waitress and general factotum”

Mary Moss, Irish, maid

Jane Story, Scottish, nurse

Nancy, nurse

Caroline, English, nurse

Levi, Black

Maria Davis, Black

Bibliography

Baltzell, Edward D. Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. Seventh Edition. New York: Free Press, 2007.

Barbour, Hugh, and William J. Frost. The Quakers. Indiana: Friends United Press, 1988.

Benjamin, Philip S. The Philadelphia Quakers in the Industrial Age, 1865-1920. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1976.

Chandler, Joseph R. “Pen and Pencil Sketches of Living Merchants – No. 1 – Thomas P. Cope, Esq. of Philadelphia. By the Hon. Joseph R. Chandler, of Pennsylvania.” The Merchant’s Magazine 20, no. 4 (1849): 355-363.

Evans, J. Morris. Tapestry Threads: Jonathan & Rachel Cope Evans 1843 to 1911, Their Ancestors & Family. Gwynedd Valley, PA, 1993.

Holst, Nancy A. Pattern Books and the Suburbanization of Germantown, Pennsylvania, in the Mid-Nineteenth Century. Dissertation, University of Delaware, 2008.

Lynch-Brennan, Margaret. The Irish Bridget : Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840-1930. Syracuse University Press, 2014.

Phillips-Cunningham, Danielle T. Putting Their Hands on Race: Irish Immigrant and Southern Black Domestic Workers. Rutgers University Press, 2020.

Scattergood, Mary Cope. A History of Awbury. Three Oaks, MI: Regnery, 1972.

Tinkcom, Harry M., and Margaret B. Tinkcom. “Germantown: Must the Present Bury the Past?” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 25, no. 2 (1958): 162-172.